Venice, Italy

projectUrban Regeneration in Venice

-

Photo by Pietro Savorelli

-

-

Photo by Alessandra Bello

-

-

Photo by Alessandra Bello

-

-

Photo by Alessandra Bello

-

-

-

-

Photo by Pietro Savorelli

-

-

Photo by Pietro Savorelli

-

-

Photo by Pietro Savorelli

-

Photo by Pietro Savorelli

-

Photo by Pietro Savorelli

-

Photo by Alessandra Bello

-

Photo by Pietro Savorelli

-

Photo by Pietro Savorelli

-

Photo by Alessandra Bello

-

Photo by Alessandra Bello

-

-

Photo by Pietro Savorelli

-

Photo by Alessandra Bello

-

Photo by Alessandra Bello

-

Photo by Pietro Savorelli

-

Photo by Pietro Savorelli

-

Photo by Alessandra Bello

BigMat Award 2017, National

Gold Medal of Italian Architecture 2012, Special Prize

In Pursuit of Architecture, Log + MoMA, 2012

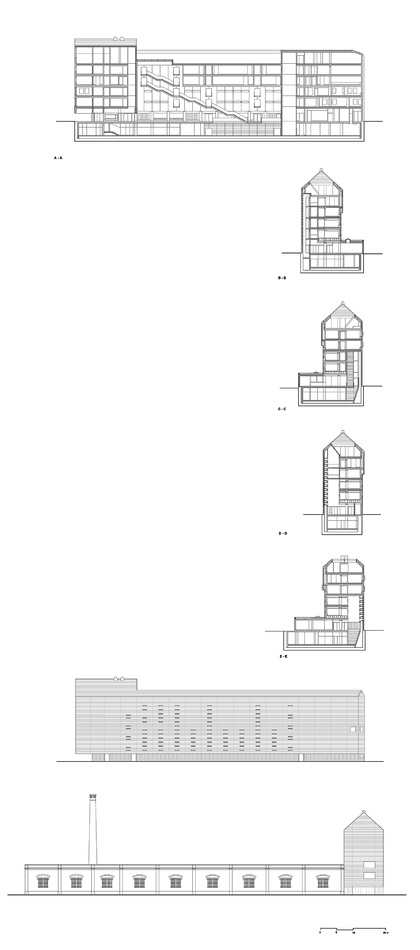

URBAN REGENERATION OF THE 19TH CENTURY TOBACCO FACTORY IN PIAZZALE ROMA FOR THE NEW CITY OF JUSTICE IN VENICE, ITALY

Design Concept

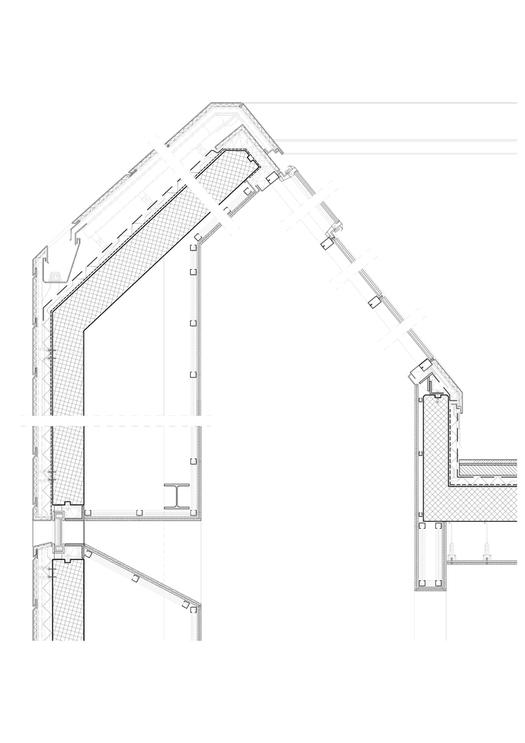

The project is the result of the conversion of an abandoned 19th century Tobacco Factory. An adaptable conversion strategy of the existing buildings is designed together with a new building in the unique, leftover open space of Piazzale Roma, while a new vaulted roof is grafted on one of the existing production spaces. The adaptive reuse strategy keeps all the existing textures of the walls and inserts a prefab steel structure, detached from the historic walls and creates a dialogue between the old and the new, as well as providing a flexible, reversible new system to inhabit the old spaces of the factory, which can be easily disassembled. A new vaulted roof is added on the existing to find more space for the assembly halls of judgement. The new building houses a hybrid typology: law-court offices, the infrastructure for the MEP on top two floors serves the entire rehabilitated factory complex; a seven-story-high interior public piazza with shops and cultural activities is a gate for the new system of campos that the restoration of the complex gives back to the Venetian citizens. The squares themselves have been designed leaving the existing green spaces to enhance biodiversity. While the scale of the new iconic volume is based on the void of Piazzale Roma and the Grand Canal, the design responds to the dense Venetian urban system beyond the plaza. The archetypical shape of the Venetian production space is stretched in length and height and grafted into the thin plot, giving identity to this regained part of the city. The introduction of a five-foot-wide technical space between the facade and the interior for the MEP, allowed us to work with natural light. The small exterior perforations become generous windows on the interior and the atrium space changes with every moment’s light and climatic condition, activating the building as much as its users do. LCV and the new vaulted roof are clad in pre-oxidized copper, which in Venice distinguishes institutional buildings.

Sustainability

Due to their mono-functional program, public buildings are often more private that the privately owned. This is the reason why, since twenty years C+S is working to open public buildings to public and allow part of them to be activated by the communities around. Thanks to this work they were able to change the policy to design school buildings in Italy as well as invited in Aravena’a 15th Venice Architecture Biennale. The LCV project operates the same strategy on a courthouse. Grafting a new building on the thin leftover space of the plot, C+S generate, on the ground floor, a public covered piazza, a place for all people, with potential cultural and community spaces to be activated by the community. This space acts also as a gate to the series of public spaces, which are given back to the Venetians. All existing trees, even the one in from of the main access are preserved, maintaining a resilient biodiverse environment in the city and creating natural shadow for the facades. Being the complex a grade 1 listed, we were able to obtain the planning permissions convincing the heritage institutions with the graft of a prefab steel structure, with the task of both consolidating the existing structures, as well as leaving a gap which defines a dialogue between the old and the new. All the interventions on the existing are reversible.

Geothermal energy and photovoltaic are used to supply the heating pumps, which are all positioned on the top of the new building, the first to be completed in 2012 in order to allow to generate energy for the whole complex. Water collection is achieved with cisterns under the public spaces, translating into contemporary a principle that allowed, in the past, a city like Venice, to survive without having drinking water, thanks to the special environmental strategy of creating public spaces for rain-water collection. The external cladding of both the new building and the vaulted one are made of pre-oxidized copper, which is 100% recyclable.

Text published in <<Log>> n. 29, 2013

Law Court Offices in Venice

Venice has no ground to be inscribed. As Carl Schmitt poetically writes, unlike the earth, which is “written” through the topographies of cultural activity and where products and rights are returned, the water, though bearing fruits, cannot be inscribed by ships, which leave no trace of their passage.

Venice is a territory constantly undergoing a process of writing and erasure in a continuous battle between human civilizations and the tide. In this condition of uncertainty, Venice has often been resistant to modernity. As Manfredo Tafuri writes in Venice and the Renaissance, “Venice is a problem for the ‘moderns.’ Fascinated by a crystallized continuity, which has been mistaken for banal organic unity – perhaps to be regained – they cannot tolerate the challenge that Venice hurls out to them. And they multiply their violent and faithless attempts, with sadistic traits that are barely hidden beneath the masks of phrases like ‘respectful project,’ ‘the past as friend,’ and the ‘new Caprice’ – masks of mummification of ephemeral revitalization.”

Venice is resistant to action as a final solution. Action here can only be an open-ended process of transformation. We reinterpret this resistance as a strategy that allows us to infiltrate the city while preserving the character of instability. Understanding all landscapes as constantly undergoing transformation, each of our projects aims to unpack the complexities of their environments through architecture – a process we call TranslationArchitecture.

In this sense, architects are the translators of context. Edouard Glissant writes that the translator necessarily invents a language which is common between two different idioms but is in some way unpredictable for both. The architect acts similarly, choosing the context to translate and presenting it in another form and time through the invention of a language that is both necessary and unforeseeable. TranslationArchitecture is a contemporary, continuous, and vital transformation of context. The LCV project exemplifies this approach.

Questioning the given site and program during the competition phase, in which architects were expected to work only on the adaptive reuse of a series of 19th-century buildings within an abandoned tobacco factory, we decided to introduce a new building. We designed a physical adapter in a unique, leftover open space in the dense urban landscape of Piazzale Roma.

We chose (and played with) the word adapter to signify a physical configuration of a translation. The word is composed of two syllables: ad and apt. We interpret apt as a soft technological element, an infrastructure necessary for a dialogue between incompatible systems. This allows connections and creates understanding without threatening the identity of each system. Ad is understood as both an addition and an advertisement, related to communication and manipulation.

LCV aims to be an adapter between programs, scales, typologies, and, from a broader perspective, between historical memory and the contemporary. While its scale is based on the huge void of Piazzale Roma, which is the car entrance to the city, and the Grand Canal, spanned here by Santiago Calatrava’s bridge, LCV responds to the dense Venetian urban system beyond the plaza. The new program proposes a hybrid typology: a building housing the law-court offices; an infrastructure housing the technological systems that form the top of LCV and will eventually serve the entire rehabilitated factory complex; and an interior piazza, a seven-story-high public entrance hall for the new system of public spaces that the restoration of the complex will return to the city.

The introduction of a five-foot-wide technical space between the facade and the interior allowed us to work with light, which in Venice is always scattered by the water. Through a soft technical solution, whereby the small exterior perforations become more generous windows on the interior, the seven-story atrium space changes with every moment’s light and climatic condition, activating the building as much as its users do. The interior space, while supporting the different programs, is perceived as a teza, a typical Venetian void space between two parallel structural walls and covered by a pitched roof. The teza is a stereometrically simple volume with various uses, including housing, storage, and boat parking.

The typological and scalar manipulation of the building is as substantial as our introduction of a new hybrid program. Sited at the end of a series of 19th-century tezas that face Piazzale Roma, LCV is a contemporary teza that connects the scale of the nearby multistory parking garages to the smaller scale of the urban texture. The compact shape of the new volume was stretched in length and height and inserted into the thin space between the historic buildings and the parking garages. On Piazzale Roma, a 16-foot-deep cantiliver that draws pedestrians inside also becomes a counterpoint to the Calatrava bridge, visually connecting the regained industrial site to the Grand Canal.

LCV is clad in pre-oxidized copper, which in Venice distinguishes institutional buildings. The building’s surface thus instigates the action of time in architecture. We don’t know if or when oxidation will turn the building the green color of the vaults that punctuate the Venetian horizon, but it is yet another translation, one that suspends LCV between the historical and the contemporary. – Carlo Cappai and Maria Alessandra Segantini

Awards

Bibliography

C+S architects, Law Court Offices in Venice, in AA.VV., Architecture Highlights, Bejin, 2014, pp. 369-372

2.6 MBC.F. Kusch, A.Gelhaar, Venice Architectural Guide, Berlin 2014, pp. 14, 38, 39, 146, 164, 210, 211, 212, 213, 214, 215

1.6 MBC+S architects, Gerichtsgebaude, in <<Baumeister>> n. 111, June 2014, p. 14.7

2.1 MBC.Cappai, M.A. Segantini, Transduction, in R. Salvi, Identity Matters. Architecture between Individualism and Homologation, Milan 2014, pp. 37-48

3.4 MBM. Biraghi, Storia dell'architettura italiana 1985-2015, Torino 2013, pp.55, 248, 249, 250, 337, 338

C.Cappai, M.A.Segantini, LCV, in <<Log>> n. 29, Fall 2013, pp. 120-131

3.1 MBC+S Architects, Law Court offices in Venice, in: <<a+a>>, Bejin, China, September 2013, pp. 28-31

7.1 MBA. Flaiano, Attrezzatura abitata. Come una lama affilata protesa verso il cielo, spicca a Venezia il nuovo Palazzo di Giustizia, in <<Progetti>> n. 6, 2013, pp. 40-47

1.3 MBC. Cappai, M.A. Segantini, The infrastructure becomes landscape design, in <<Zeppelin>> n. 115, 2013, pp. 55-71

3.5 MBC. Molteni, Traduzione di un contesto. Translation of a context, in <<OFARCH>> n. 125, 2013, pp. 46-53

3.0 MBD. Nezosi, Law-court offices in Venezia, Italy, in <<Arketipo>> n. 73/13, 2013, pp. 66-77

3.9 MBS. Carta, Fitted law court offices, Venice, in: <<A10>> n. 50, 2013, pp. 18-20

2.4 MBC+S-Cappai Segantini, TranslationArchitecture, in: <<IoArch>> n. 46, 2013, pp. 23-32

3.8 MBF. Irace, Mediterranean Calligraphies. Italy, the Balkans and Greece, Paths to Identity, in L. Fernandez-Galiano, Atlas. Europe. Architecture of the 21st Century, Bilbao 2012, pp. 52-61, 74-75

1.5 MBF. Irace, Justice is done. New Signs in the Old City, in <<Domus>> n. 964, December 2012, pp. 72-77

2.6 MBC.Cappai, M.A. Segantini, LCV. Law-Court Offices in Venice, PPS. Ponzano Primary School, HBB. Harbor Brain Building, in: AA.VV., Gold Medal of Italian Architecture, catalogue of the exhibition, Bologna 2012, pp. 78-83, 138-139, 198-199

5.5 MBF. Irace, Italia construye. Global and Contextual: a New Generation, in: <<Arquitectura Viva. Italian Beauty. Between Craftmanship and Context.>> n. 160, February 2014, pp. 11-19, 44-47

1.8 MB

Credits

Architects: C+S Architects, Carlo Cappai, Maria Alessandra Segantini

Design Team: Davide Testi, Barbara Acciari, Monica Moro

Masterplan: C+S Architects, Studio CM, Technimont spa

Detailed, Structural and Plant Engineering: Technimont, Studio Greggio, Progin

Client: Comune di Venezia

Built area: 54.000 m² (gross)

Budget: 64M euro

Competition: March 1999

Design phase: September 1999-February 2002

Construction phase (beginning and ending month, year): September 2002-June 2012